Written by Saori Takeda:Publisher and Editor-in-chief, ART Driven Tokyo

Acrylic on board, in 2 parts Overall: 57 5/16 × 81 1/8 inches (145.6 × 206 cm)

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Courtesy the artist, Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, and Gagosian

He is called ‘The Painter of Sorrow’ in Japan. Died at 31, had dreamed of a show in NYC

Tetsuya Ishida is a Japanese painter who explores the difficulties of modern life to the level of the unconscious and forces his audience to reflect on life through his exquisite figurative works. His solo exhibition My Anxious Self is being held at Gagosian in Chelsea, NY, one of the prestigious commercial galleries in the world, until October 21, 2023. More than 80 of his approximately 200 total works are on display. 31-year-old Ishida (1973-2005) died in an accident, and his dream was to have a solo exhibition in Europe and the U.S. Ishida’s wallet, which he kept until the end of his life, contained several American dollar bills. In Japan, there is a custom of “omamori” (good luck charm), which means that if you always wear a lucky item, your wish will come true.(The exhibition ended.)

This is the first comprehensive exhibition of Ishida‘s work outside of Japan to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his birth. ART Driven Tokyo’s mission is to introduce exceptional Japanese contemporary artists into the world and change the history of art in a Zen-like spirit. I feel like a sense of destiny that our first article is about Ishida‘s solo exhibition at Gagosian. We will introduce the meaningful traces Ishida has left in this world through his works, while deeply examining on his strong message.

Photo: Rob McKeever

Courtesy Gagosian

My Anxious Self-Depression since birth, no reward for hard work. Self-portraits of Japanese people

Nick Simunovic, senior director of Gagosian in Asia says, “We had an impressive turnout on opening night September 12 with over 600 visitors in attendance, including notable collectors and curators. The response has been incredibly positive with visitors eager to learn about Tetsuya and his work.”

Ishida emerged as an artist during Japan’s “Lost Decade,” a recession that lasted through the 1990s, and his paintings capture the feelings of hopelessness, claustrophobia, disconnection that characterized Japanese society during this time—even in the wake of its rapid technological advancement.

Disconnection, alienation and despair.

New York audiences empathize with Ishida’s healing fantasy

Refuel Meal, 1996-The workers are eating like robots, refueling at a restaurant chain. The workers’ gazes seem unfocused and ill. They express the dangers of a mass consumer society and a sense of alienation.

Ishida said, “At first, it was a self-portrait. I tried to make myself—my weak self, my pitiful self, my anxious self—into a joke or something funny that could be laughed at. It was sometimes seen as a parody or satire referring to contemporary people. As I continued to think about this, I expanded it to include consumers, city-dwellers, workers, and the Japanese people.”

Ishida‘s satire – the inability to escape the oppression of organizations such as companies and schools that force one to lose one’s self, the lack belonging, and the difficulty of living – is something that any Japanese person can understand. And now, art fans not only in Asia but also in Europe and the United States are fascinated by this world of deep sadness.

Simunovic says, “Not at all surprisingly, Tetsuya’s work has found a very receptive audience in New York. The profound humanity of his paintings addresses themes that are not only universal – disconnection, alienation and despair – but speak to the exact age in which we live. In some respects, his acknowledgment of the impact of machines and technology resonates and feels more urgent now than in the late 1990s when the works were first made. Simunovic also says, “We believe in his work and feel it’s extremely important that it be seen and understood in the West.”

Courtesy Gagosian

Overly concrete dream of becoming a deformity: Source of creativity

Gripe, 1996, acrylic on board, 23 3/8 × 16 5/8 inches (59.4 × 42 cm) – In Japanese train stations, station staff used to poke holes in customers’ tickets to let them through the ticket gates. The uniformed station attendant’s hands were crayfish, holding the ticket and trying to cut it. The labor of cutting tickets from morning to night disappeared after the restructuring that accompanied the privatization of the state-run railroad, and many station staff lost their jobs. The helplessness of the station clerks, who have become an oddly shaped thing, and the sadness of the urban workers are conveyed in this work.

The most distinctive feature of Ishida‘s work is surrealism, in which humans are fused with animals and objects. According to the Japanese national broadcaster NHK’s art program “Sorrow Canvas: The World of Tetsuya Ishida,” broadcast in 2006, Ishida sometimes dreamed about the fusion of animals and humans, such as a dream in which a human was born from a dinosaur, and he used the dreams in his works.

16 5/8 x 23 3/8 inches (42 x 59.4 cm)

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Photo: Martin Wong

Courtesy Gagosian

Irony and parody of physical labor for survival

Gripe, 1997, Acrylic and oil mounted on board, 16 5/8 x 23 3/8 inches (42 x 59.4 cm)-Human being is united with construction vehicle, bound and forced to labor. The inescapable sadness is expressed to the extreme, even to the level of the unconscious to the point of romanticism.

The audience is forced to superimpose themselves on this human vehicle, to confront and contemplate the crisis of dehumanization that they has been trying not to see. Is it okay for human beings to push this materialism further? Is there a place to escape? Even though human beings is headed for destruction, is it okay to pretend we don’t see it?

Ishida was in struggling to earn a living, doing hard physical labor, including working as a security guard at a construction site; according to NHK’s Sorrow Canvas, Ishida‘s mother offered to help, but Ishida turned it down in order to become more self-reliant.

Ishida is objective in his own grief and does not drag the audience into negativity. Ishida may have tried to hold on to his humanity by turning his hard labor into an ironic laugh, a parody.

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Photo: Rob McKeever

Courtesy Gagosian

Overall: 57 3/8 × 81 1/8 inches (145.6 × 206 cm)

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Photo: Martin Wong

Courtesy Gagosian

A blank gaze discusses: Live like robots or prisoner and die like mass product. Is that really enough?

Recalled, 1998, Acrylic on board, in 2 parts, overall: 57 3/8 × 81 1/8 inches (145.6 × 206 cm)-The funeral casket is the box that contained the television. The body is stored neatly and orderly, like the parts of a plastic model. The final resting place of an assembly line worker is in a cardboard box, just like a mass-produced product.

Ishida’s works were discovered in large quantities after his death. Ishida‘s life tends to emphasize the dramatic aspects of his difficulties, but of course he must have been very happy when he was painting. The works, painted only 10 years after graduating from a renowned Japanese art university, are often large and painted in tight perspective. The drafting alone must have required a great deal of effort. Ishida sublimated his sadness into a sarcastic laugh. He was quite an energetic and serious artist.

40 5/8 × 57 3/8 inches (103 × 145.6 cm)

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Prisoner, 1999, Acrylic on board,40 5/8 × 57 3/8 inches (103 × 145.6 cm)- A human tied to the school building and unable to move. The schoolyard is sparsely populated with children, which accentuates the pain of the situation.

Overall: 57 3/8 × 81 1/8 inches (145.6 × 206 cm)

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Courtesy the artist, Kyuryudo Art Publishing, and Gagosian

Not good at socializing. But always draw human beings. Why?

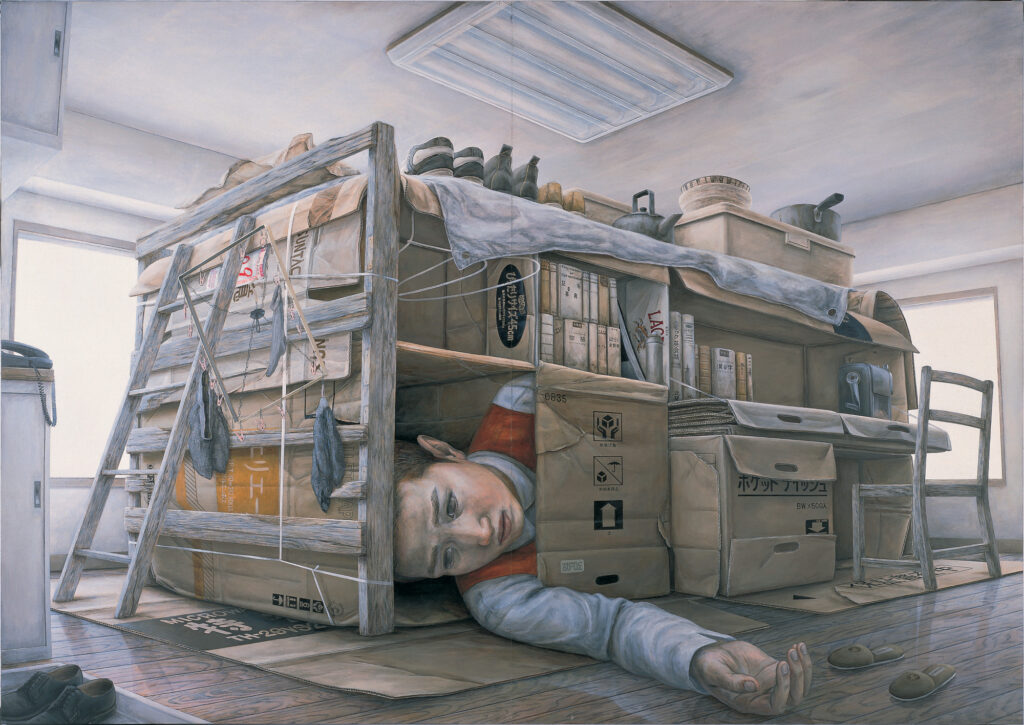

Untitled, 1998, Acrylic on canvas, in 2 parts, overall: 57 3/8 × 81 1/8 inches (145.6 × 206 cm)-The furniture is a study desk under the bed, which is common in Japanese households with small land and small dwellings. The person depicted is to move, too. The blank gaze expresses the ultimate despair.

Every artwork is a portrait of the artist himself, and Ishida himself says so, but his works are talkative, in complete contrast to his overly taciturn personality.

Diethard Leopold, cofounder and curator of the Leopold Museum, Vienna, and a former psychotherapist, examines Ishida’s frequent use of his own face in his paintings. Leopold says in the catalogue book of this show, “This notably un-Japanese strategy is applied, he argues, not for the purposes of self-portraiture, but instead as a tool for critical observation of the common “salaryman.”

Ishida says he was never good at socializing. However, he has always drawn people. Why is this? If he really disliked people, why would he draw them?

NHK’s Sorrow Canvas reported that Ishida used movies as a reference for his work, meticulously writing down his viewing notes. After seeing the movie Betty Blue, Ishida wrote his impression of the movie, “The characters in the film are constantly moving. It leads to sadness and a changing landscape. Human relationships that are changing,” It is apparent that he is very interested in people and human relationships.

He was interested in others. He wanted to build good relationships with others. He must have made a great effort for that. I think, Ishida is a very stoic person.

17 7/8 × 20 7/8 inches (45.4 × 53 cm)

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Fantastic, illustrative paintings are just right for in this day and age.

The timing was not right. Ishida emerged a little too early.

Untitled, 2004, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 17 7/8 × 20 7/8 inches (45.4 × 53 cm)-What a powerful, clearly expressed and artistic Memento Mori it is! In his later years, Ishida suffered from liver disease. It is common for painters to become anxious at times, whether while painting or in the midst of life, but Ishida faced and expressed the cold, transparent anxiety of death.

In the 1990s, Ishida was trying to make his mark in Europe and the United States, winning famous Japanese awards for illustration art and painting, and belonging to a gallery in Ginza, one of Japan’s leading art districts. Now, a couple of decades later, Ishida‘s work is just right for art lovers around the world: contemporary art in the early 21st century is shifting from conceptual to figurative painting. Audiences are shifting their preference from overly intellectualized conceptual art to accessible figurative art. When Ishida died in 2005, the world art scene was still in its conceptual heyday. Although illustration art is now highly acclaimed thanks to the success of Yoshitomo Nara, the status of illustration was not so high at the time.

The timing was not right. Ishida emerged a little too early.

ART Driven Tokyo is proud of Ishida.We’ll introduce Japanese artists who may change the world history of art.

Many talented Japanese artists with delicate craftsmanship and a pop, fantastical, yet profound spirituality are struggling to find opportunities despite winning famous prizes. I have seen many, many Japanese artists give up painting and pursue other careers. We, Art Driven Tokyo was launched to change this situation.

I hope that as many Japanese artists as possible will hold solo exhibitions at Gagosian, Pace, and Perrotin, like Ishida, and I am confident that the day will come soon.

© Tetsuya Ishida Estate

Photo: Rob McKeever

Courtesy Gagosian

Exibition overview

Tetsuya Ishida My Anxious Self, curated by Cecilia Alemani

September 12-October 21, 2023, 555 West 24th Street, New York

Hours: Tuesday–Saturday 10–6

Tetsuya Ishida

Born in Yaizu, Japan, in 1973, and died in Sagamihara, Japan, in 2005. Solo exhibitions include Sumpu Museum, Shizuoka, Japan (2006); Canvas of Sadness, Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art, Japan (2007); CB Collection, Tokyo (2007); Self-Portraits of Ourselves, Nerima Art Museum, Tokyo (2008); and Notes, Evidence of Dreams, Ashikaga Museum of Art (2013, traveled in Japan to Hiratsuka Museum of Art; Tonami Art Museum, Toyama; and Shizuoka Prefectural Museum of Art through 2014); Saving the World with a Brushstroke, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (2014–15); and Self-Portrait of Other, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (2019, traveled to Wrightwood 659, Chicago). Ishida’s work was also included in the 4th Yokohama Triennale (2011), 10th Gwangju Biennale (2014), and 56th Biennale di Venezia (2015).

The catalogue book Tetsuya Ishida: My Anxious Self

Contact: Gagosian

collecting@gagosian.com